A Good WW1 Royal Navy Battle of Jutland H.M.S. Warspite (The ‘Grand Old Lady’ of the Fleet) 1914/15 Star Trio & Special Constabulary Medal Group to J.9992 Stoker A. E. Brailey (1567)

A Good WW1 Royal Navy Battle of Jutland H.M.S. Warspite (The ‘Grand Old Lady’ of the Fleet) 1914/15 Star Trio & Special Constabulary Medal Group to J.9992 Stoker A. E. Brailey (1567)

A Good WW1 Royal Navy Battle of Jutland H.M.S. Warspite (The ‘Grand Old Lady’ of the Fleet) 1914/15 Star Trio & Special Constabulary Medal Group awarded to J.9992 Stoker A. E. Brailey

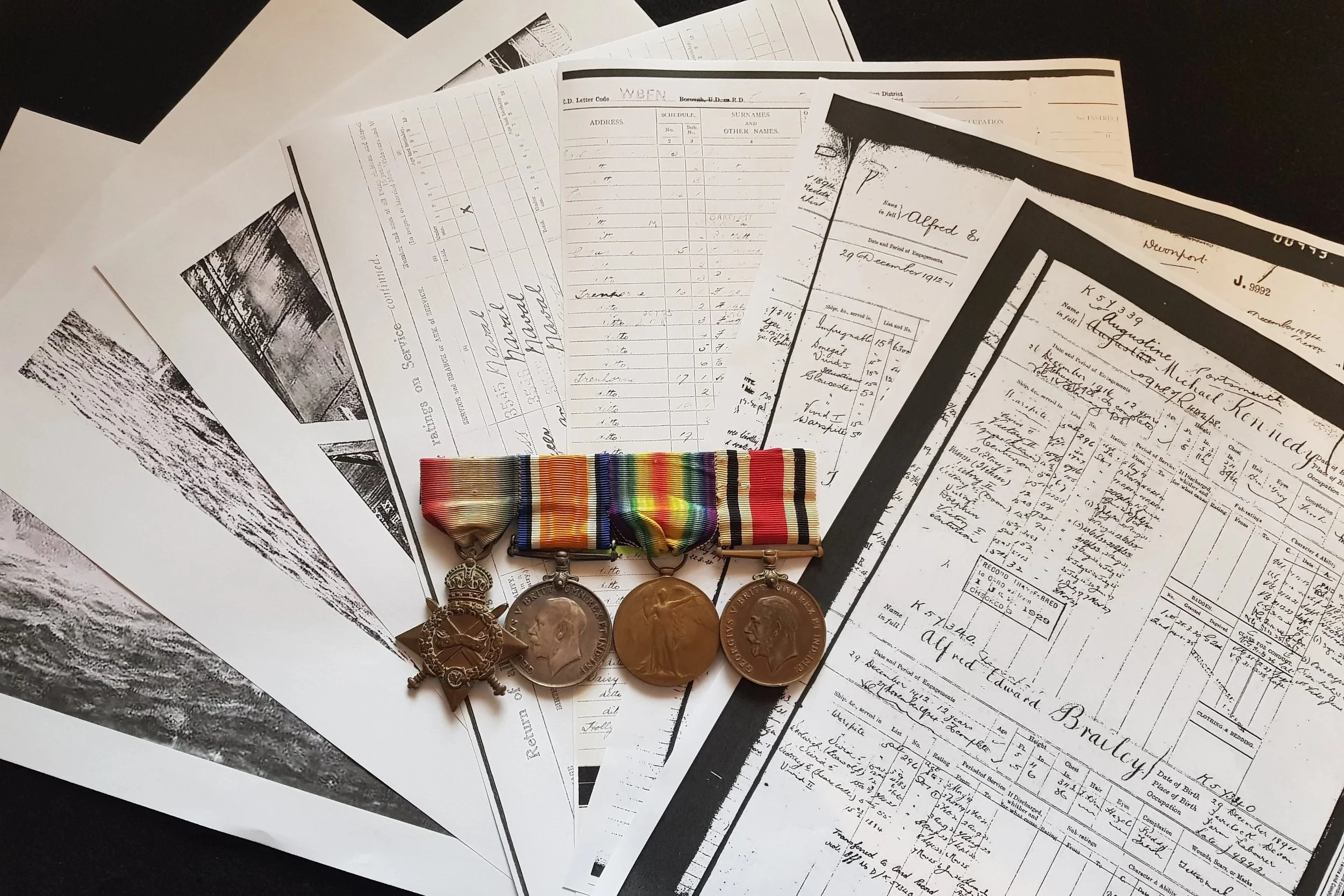

1914-15 Star (J.9992 A. E. Brailey. A.B., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (J.9992. A. E. Brailey. A.B., R.N.); Special Constabulary Long Service Medal, G.V.R. (Alfred T. Brailey.), evidence of cleaning, contact marks and edge wear overall, nearly very fine (4)

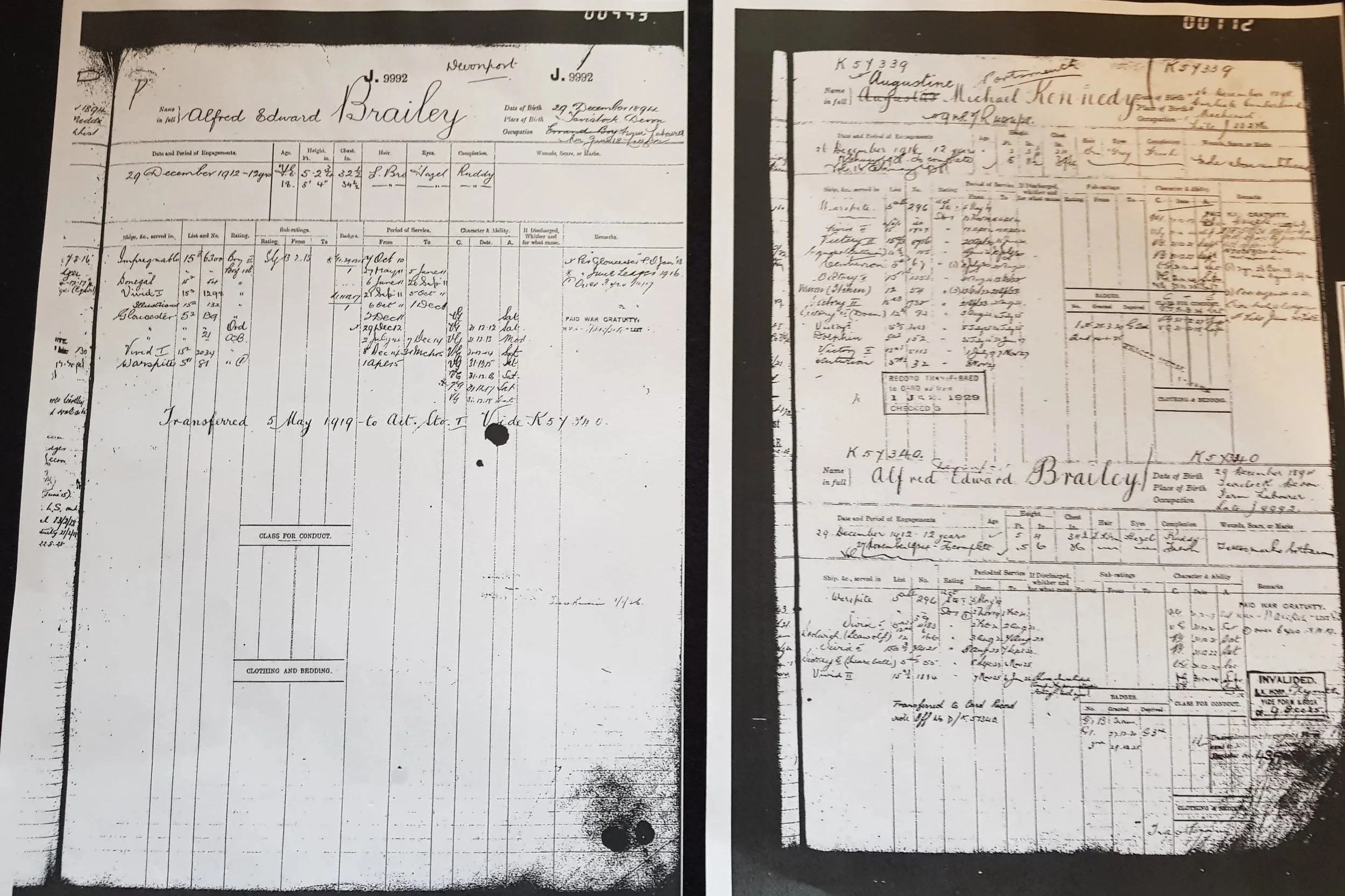

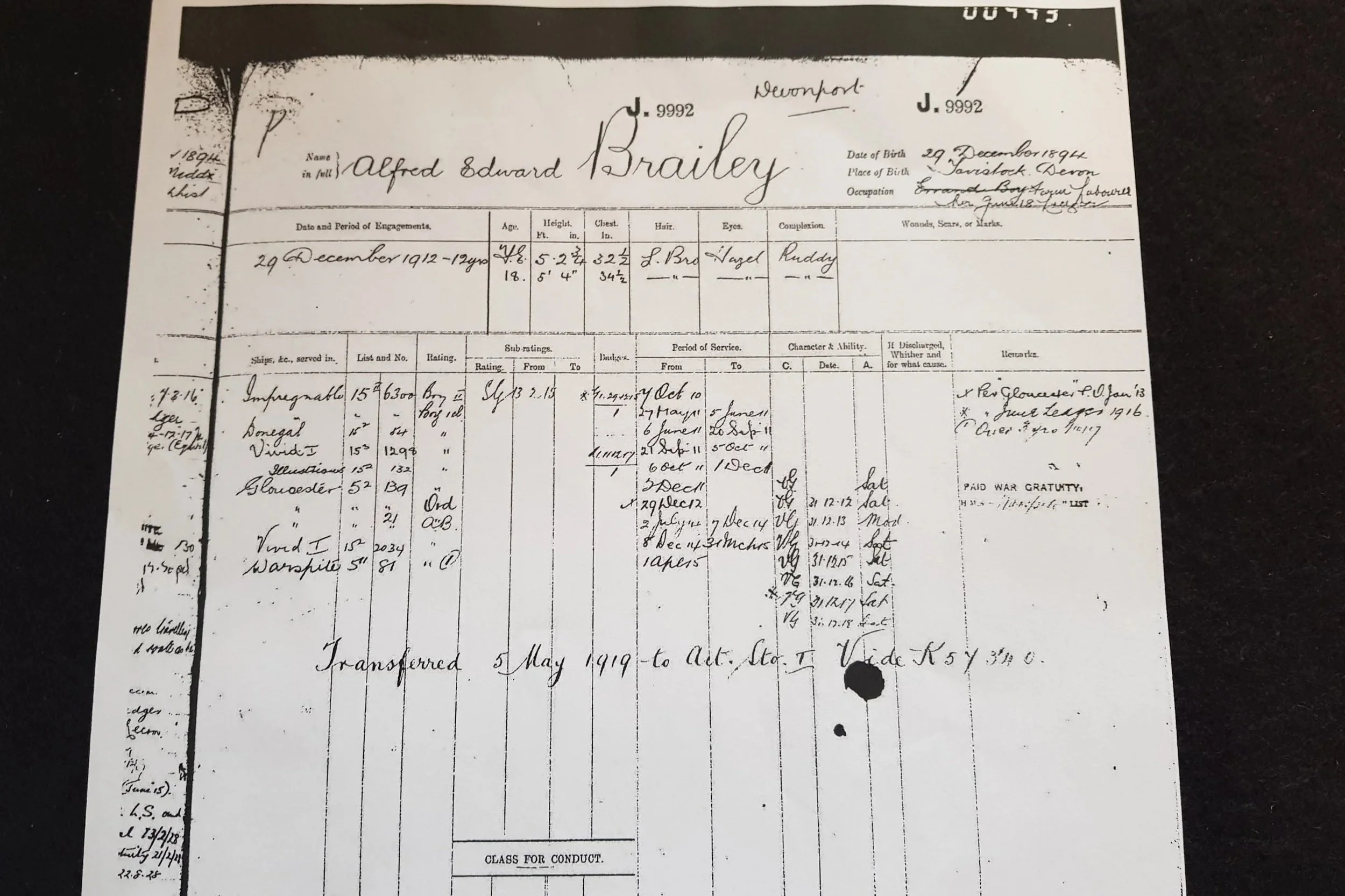

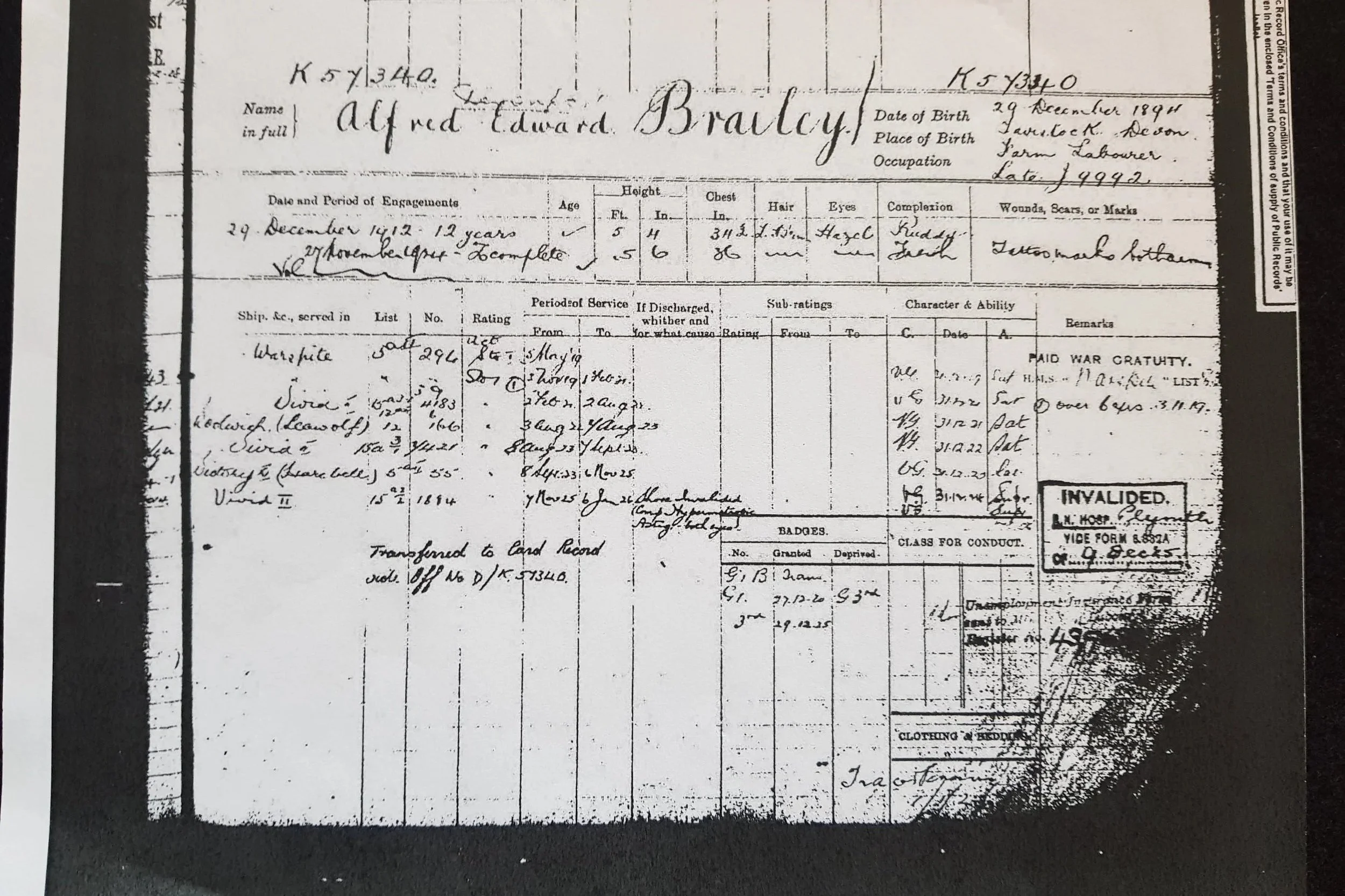

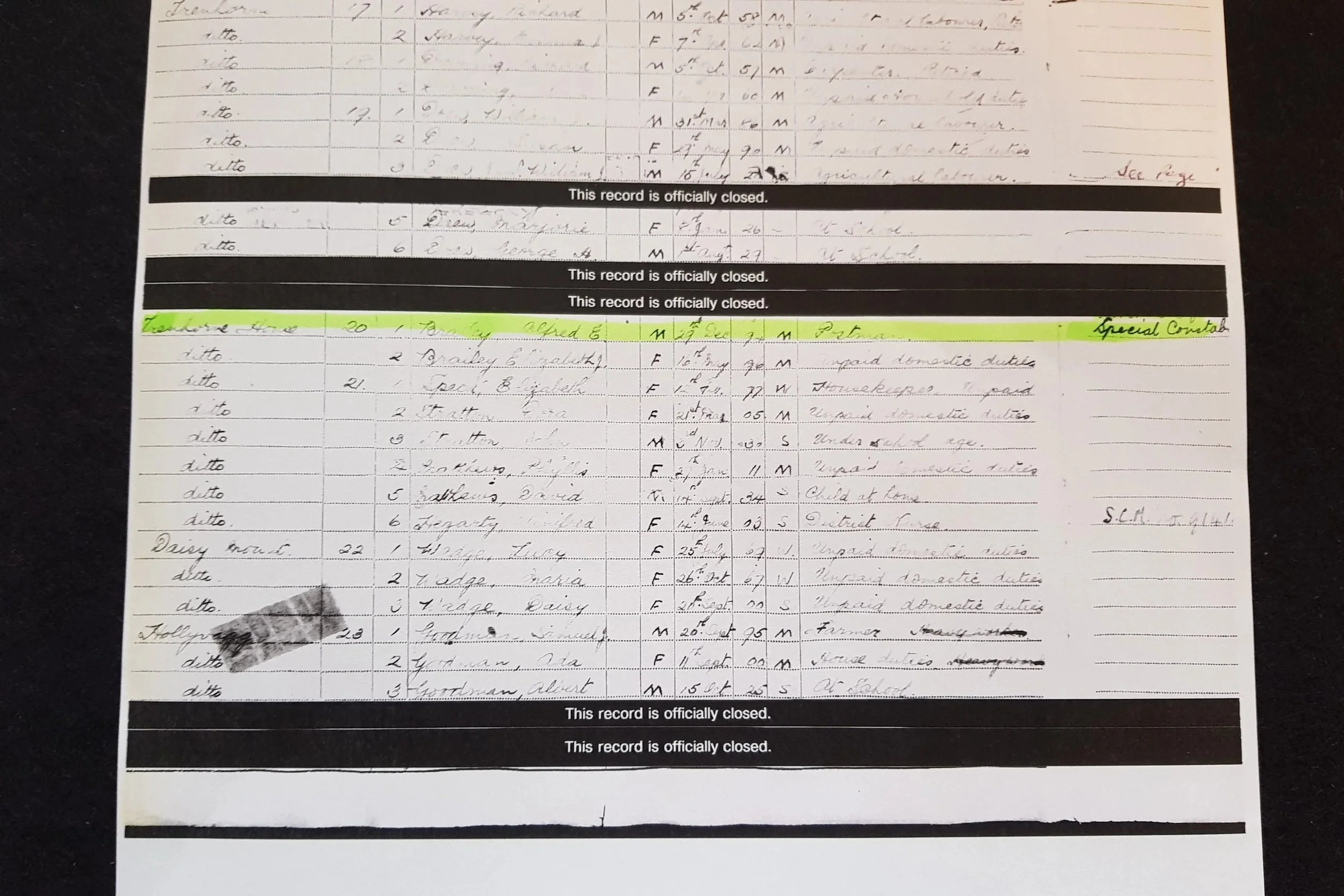

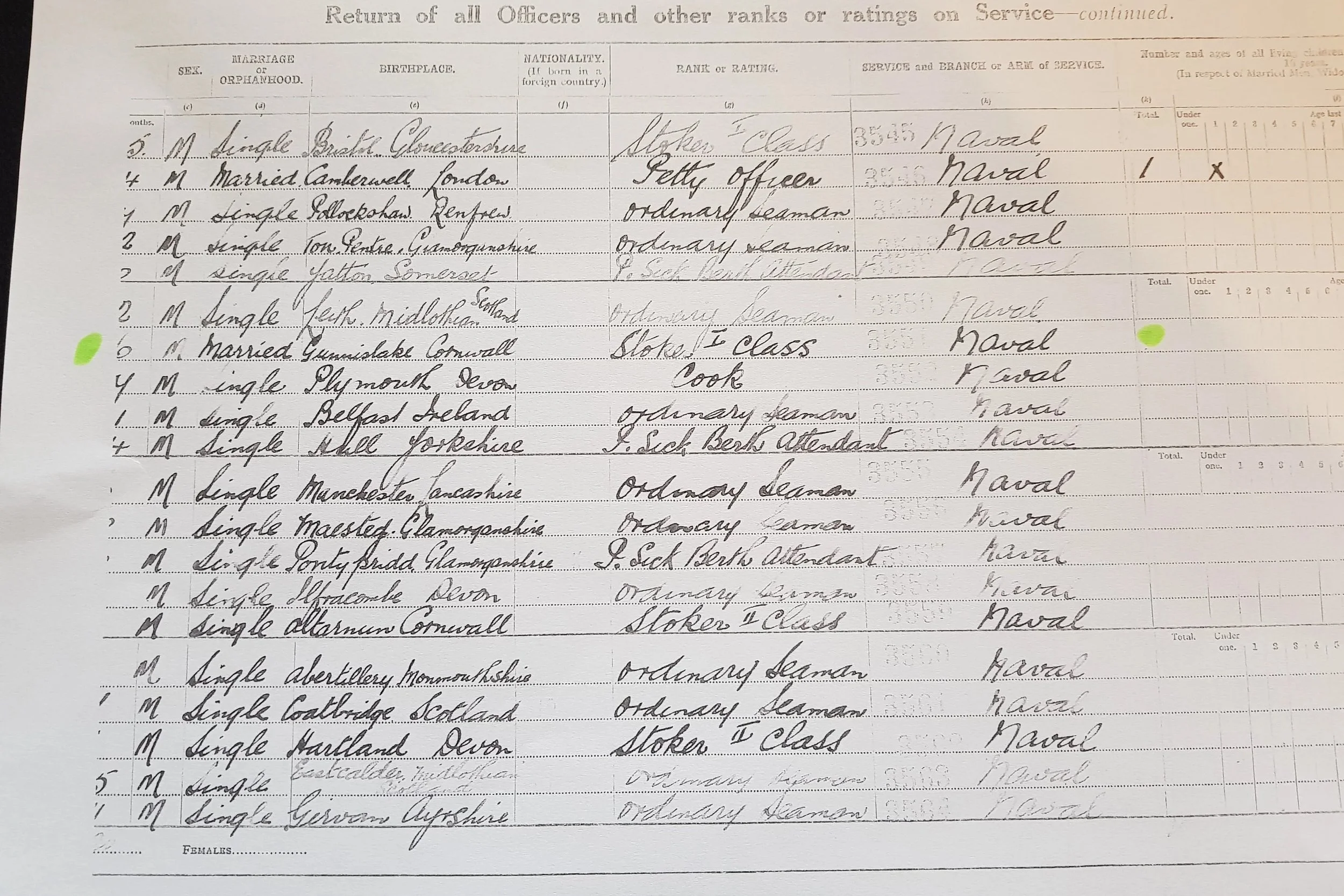

Alfred Edward Brailey was born at Tavistock, Devon on 29 December 1894 and entered the Royal Navy on 7 October 1910 with the rank of Boy Class II. Reaching his majority with Gloucester in 1912 he was advanced Able Seaman in 1914 with this vessel, entering the war with her. Seeing his first action during the Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau Brailey was transferred to the Queen Elizabeth class Battlecruiser Warspite on 1 April 1915.

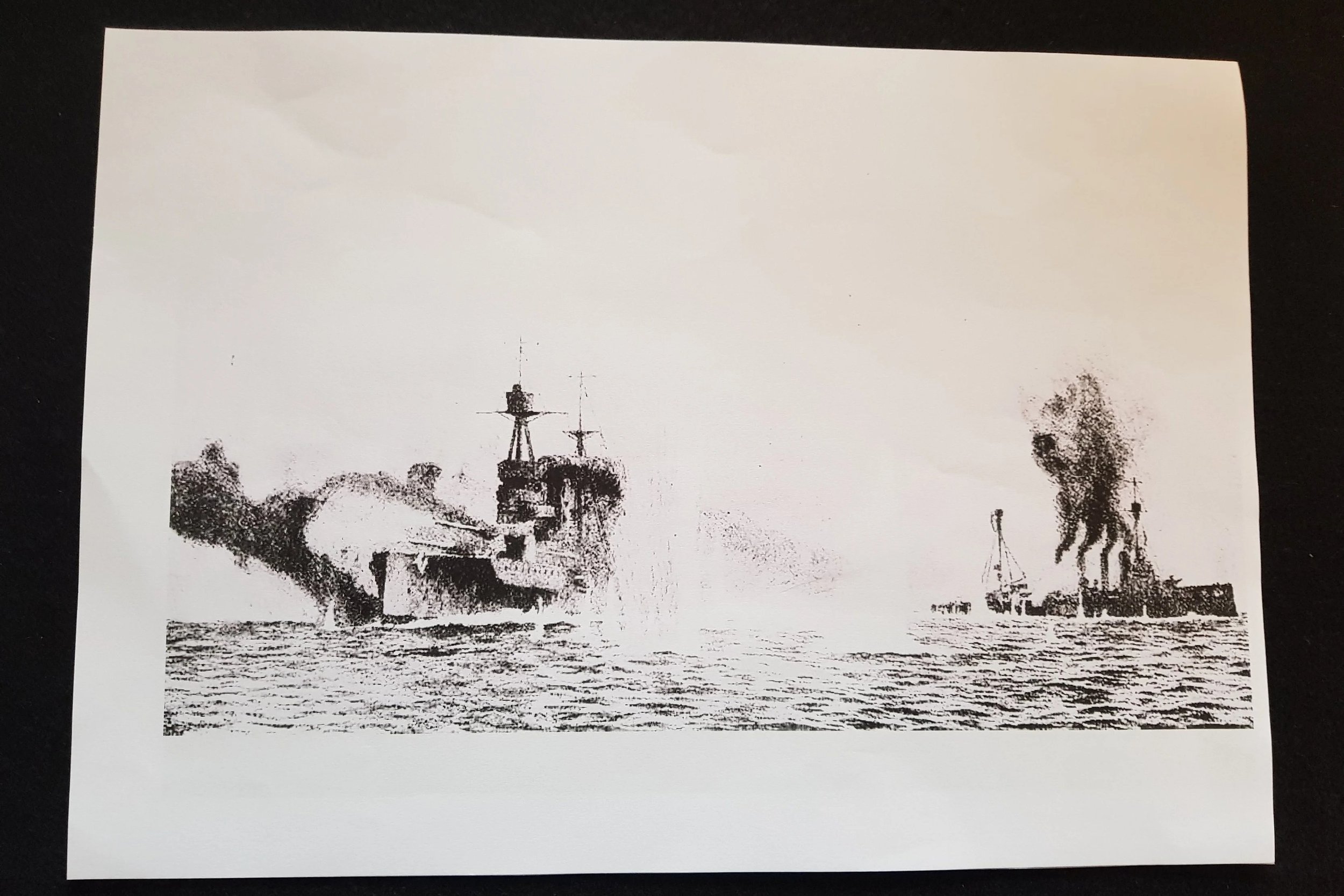

Jutland -

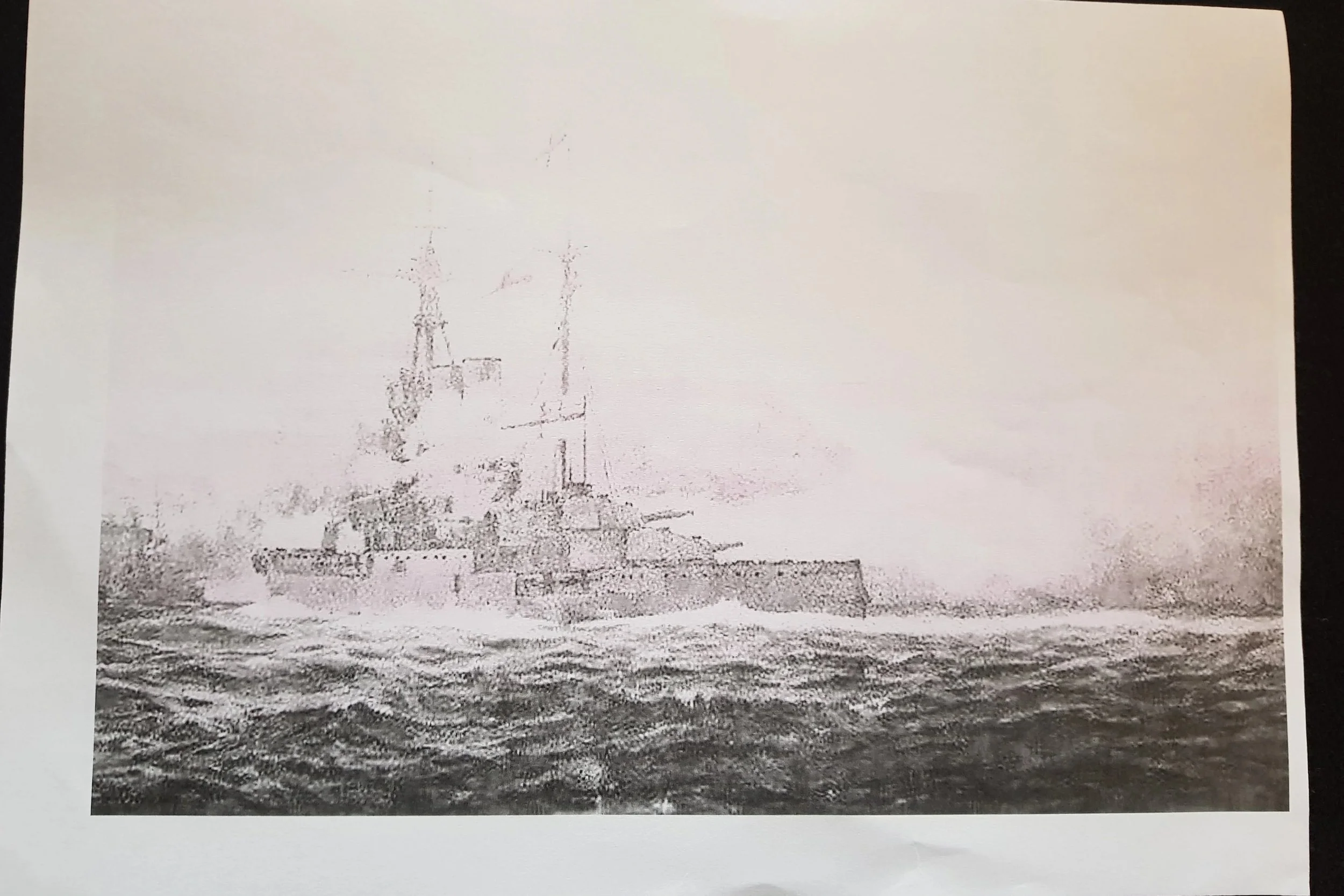

Commanded by Captain E. M. Philpotts, R.N. - and boasting her prescient motto 'I Despise the Hard Knocks of War' - Warspite's armoury included four twin 15-inch guns. She was of revolutionary design and capable of 24 knots, even with her robust armoured plating which in the 'vitals' was 13-inches-thick.

Quite a few eye-witness accounts of Warspite's part in that famous battle survive, but by way of summary of her experiences the following extract is taken from Chris Bilham's The Jutland Honours (Spink, 2020):

'At 14:30 hrs on 31 May 1916 5 BS was five miles astern of Lion, and had just commenced a turn to the north to rendezvous with Jellicoe, when the enemy was sighted. Lion immediately executed a turn to the south-east, at the same time signalling by flag for the other ships to do so. However, because of the distance and the heavy smoke produced by the battle-cruisers when travelling at speed, Lion's signal was not seen. Therefore, although Admiral Evan-Thomas, commanding 5 BS, saw the battle-cruisers turning away, he assumed that Beatty wanted him to maintain the course he was on. It was nearly ten minutes before Beatty noticed that 5 BS was not following and signalled Evan-Thomas to join him; by that time, the distance between the two groups of ships was ten miles. Beatty could still have slowed down to allow time for 5 BS to join him but it was not in his nature to do so when the enemy was in sight and so the Battle Cruiser Fleet went into action at 15:45 with only six capital ships instead of ten. This was one of the critical errors which cost the British a decisive victory.

By 16:10 hrs 5 BS was within range of the rear-most ships in the German line and opened fire at the extreme range of 19,000 yards. Fresh from their training under Jellicoe's meticulous eye, it was one of the most accurate-shooting squadrons in the Grand Fleet and soon 15-inch shells were raining down on the German ships. Von der Tann and Moltke were both hit and suffered serious damage. Admiral Scheer wrote 'Superiority in firing and tactical advantages of position were decidedly on our side until 4:19 pm when a new unit of four or five ships of the Queen Elizabeth type, with a considerable surplus of speed, drew up from a north-westerly direction and … joined in the fighting. It was the English 5th Battle Squadron. This made the situation critical for our battle-cruisers. The new enemy fired with extraordinary rapidity and accuracy'.

At this stage of the battle, known as 'The Run to the South', Hipper and the German battle-cruisers were luring Beatty and his ships towards the main German battle fleet, approaching from the south. Every ninety seconds brought the British one mile closer to the sixteen dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet.

At 16:35 the British light cruisers reported the presence of the High Seas Fleet to Beatty, who continued on his south-east course for two more minutes until he could see the masts of the German battleships twelve miles away. Then, at 16:40 hrs, the battle-cruisers reversed course to the north-west. Now the roles had changed, and Beatty was luring the Germans towards Jellicoe and the guns of the Grand Fleet, still more than 40 miles to the north. This phase of the battle, which lasted for about an hour, is referred to as 'The Run to the North'.

When the battle-cruisers changed course, another communications error occurred and the order was not passed to 5 BS until 16:57, fully a quarter of an hour after Lion had done so. With the two fleets steaming towards each other at full speed this was enough time to bring 5 BS well within range of the High Seas Fleet. To compound the error, the ships were ordered to turn in succession, rather than together; the Germans concentrated their fire on the turning point and Warspite was hit three times. As 5 BS carried out its belated turn, an officer in Malaya observed 'that our battle cruisers, proceeding northerly at full speed in close action with the German battle cruisers, were already quite 7,000 or 8,000 yards ahead of us. I then realised that just the four of us of the 5th BS alone would have to entertain the High Seas Fleet - four against perhaps twenty. The enemy continued to fire rapidly at us during and after the turn'.

Warspite and her sisters formed the rear-guard of the Battle Cruiser Fleet. Warspite and Malaya concentrated on the leading ships of the High Seas Fleet while the other two fired on the rear-most German battle cruisers. Warspite's Executive Officer wrote 'Very soon after the turn I saw on our starboard quarter the whole of the High Seas Fleet-masts, funnels and an endless ripple of orange flashes all down the line… I distinctly saw two of our salvoes hit the leading German battleship. Sheets of yellow flame went right over her masts and she looked red fore and aft like a burning haystack. I know we hit her hard.'

Warspite and Malaya obtained a number of hits on Konig and two other battleships, but were themselves hard hit. This was the most dangerous stage of the battle for Warspite; if there had been any damage to her propulsion machinery she would have fallen behind to be destroyed by an over-whelming force of the enemy, as happened to Blucher at the Dogger Bank. Warspite's Executive Officer was sent to inspect the damage and Gordon comments 'His 26 page narrative of his between-decks steeplechase around the battleship's accumulating scenes of carnage - with its terse references to fire, smoke, darkness, chasms awaiting the unwary, escaping steam, electrical shocks, flooding, terrible injuries and incidental absurdities - provides a nightmare glimpse of the realities of modern naval action'.

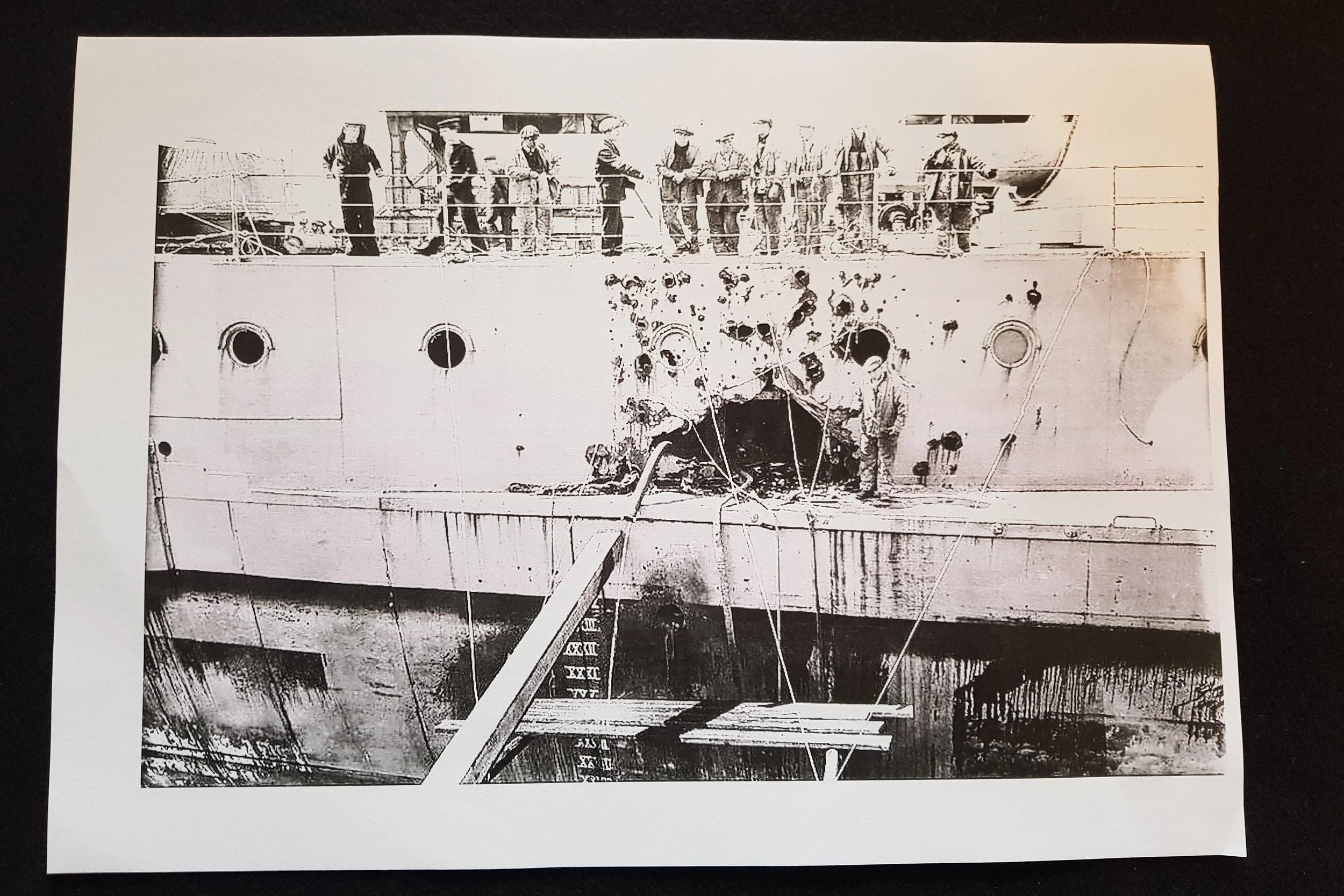

The 'Run to the North' came to an end at about 18:00 when the Battle Cruiser Fleet sighted the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe then executed a complicated manoeuvre, changing from cruising formation (in columns) to a single line of 24 battleships. 5 BS attempted to form astern of the others but, at this critical juncture, Warspite's helm jammed and she found herself charging the enemy fleet alone. She closed to within 12,000 meters of the enemy line and was hit by at least seven heavy calibre shells. Her Captain decided to continue the turn to starboard and completed two full circles before recovering control of his ship. Warspite's bizarre manoeuvre at least had the beneficial effect of drawing off fire from the crippled armoured cruiser Warrior, enabling her to escape.

At this stage, severely damaged and with unreliable steering gear, Warspite was ordered to return to Rosyth. Even then, she was not out of danger; at 09:35 on the morning of 1 June, she observed two torpedoes which passed close to the ship, one on either side, and there were two more encounters with submarines before she finally docked at 15:15 hrs. Considering the damage she had sustained, her casualties were remarkably light: fourteen men killed and thirty-two wounded. She stayed in dock until 4 July.'

Post War -

Transferring to serve as Stoker in 1919 Brailey was posted ashore that same year and joined the crew of Seawolf in August 1922. He continued to serve until August 1926 when he was invalided ashore, his early exit from the service prevented him from claiming an L.S. & G.C.

The 1921 Census shows Alfred employed as a Stoker 1st Class, Naval, at Gunnislake, Cornwall, and post war, Alfred worked as a postman a Special Constable serving with the Cornish Constabulary living in Launceston, Cornwall – 1939 Census refers.

The medals are mounted for display, sold with copied research confirming all of the above, and are as follows –

1914-15 Star, J.9992 A. E. BRAILEY. A.B., R.N.; British War and Victory Medals J.9992. A. E. BRAILEY. A.B., R.N.; Special Constabulary Long Service Medal, G.V.R. ALFRED T. BRAILY.

Condition, evidence of cleaning, contact marks and edge wear overall, nearly very fine

Please note the incorrect initial and surname spelling on the Special Constabulary Medal (T not E & BRAILY not BRAILEY).